I found my granddaughter in a marina parking lot, barely alive. She whispered It was Adrian… th…

The Broken Doll at Dawn

The Broken Doll at Dawn

I found my granddaughter Natalie in the marina parking lot at dawn, crumpled beside her car like a broken doll. Her blonde hair was matted with blood, and her left arm was twisted at an angle that made my stomach turn.

The November wind off the Atlantic cut through my jacket as I dropped to my knees beside her. My old hands were shaking as I checked for a pulse.

“Natalie baby, it’s grandma, stay with me.”

Her eyes fluttered open, unfocused and glassy. Her lips moved, barely a whisper.

I had to lean in close to hear her over the sound of waves crashing against the dock.

“Grandma, it was Adrien,” she breathed.

He said, “Our kind doesn’t belong in his world.”

“The Carmichaels, they paid him to.”

Her eyes rolled back and she went limp in my arms. I screamed for help until my throat was raw.

A fisherman running to his boat heard me and called 911. As the sirens wailed closer, I held my granddaughter’s hand and felt something inside me shift—not break, but harden, and turn to steel.

The Invisible Observers

My name is Dorothy Walsh, and I’m 67 years old. I’ve cleaned houses for wealthy families in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, for 43 years.

I raised three kids after my husband died young. I know what it means to be invisible to people who have money.

But what those people don’t know, what the Carmichael family would never suspect, is that invisible people see everything. Natalie survived the first night with a broken arm, cracked ribs, a severe concussion, and internal bleeding.

The doctor said if I’d found her 20 minutes later, she would have died from hypothermia on top of everything else. My daughter Rebecca, Natalie’s mother, flew up from Boston.

We took turns at her bedside in Maine Medical Center, watching monitors beep and medications drip. The police came on day two: Detective Maria Santos, mid-40s with sharp eyes that missed nothing.

“Mrs. Walsh, your granddaughter mentioned someone named Adrien before she lost consciousness. Can you tell me about him?”

“Her husband,” I said, the word tasting bitter.

“Adrien Carmichael. They’ve been married 14 months.”

A Legacy of Old Money

“The Carmichael family?” Detective Santos’s eyebrows rose.

“Old Harbor Road?”

The same. Everyone in Cape Elizabeth knew the Carmichaels.

Four generations of old money, the kind that owned half the waterfront and had their names on hospital wings and library buildings. Adrien’s grandfather had been a shipping magnate.

His father, Richard Carmichael, now ran a private equity firm and sat on every board that mattered.

“We’ll need to bring him in for questioning,” Detective Santos said.

“Good luck with that,” I muttered.

“The Carmichaels have lawyers like normal people have relatives.”

Sure enough, within six hours, Adrien showed up at the hospital with two attorneys. They wouldn’t let us near him, but I saw him through the waiting room window.

He was in a perfectly pressed suit, not a hair out of place, with an expensive watch catching the fluorescent lights. He looked worried in that distant way people look when they’re performing concern.

Secrets in the Attic

When Natalie woke up three days later, she couldn’t remember anything after leaving work. The doctor said it was common with head trauma.

The police found her car keys in her pocket, with no sign of break-in or struggle except for her injuries. Adrien claimed he’d been at a business dinner in Portland 20 minutes away with witnesses.

The timeline made it possible for him to have done it and still made his alibi, but barely. Without Natalie’s memory, they couldn’t charge him with anything.

But I remembered what she’d said to me in that parking lot: the Carmichaels paid him. Rebecca wanted to take Natalie back to Boston, away from Adrien and his family.

But Natalie, once she could talk, insisted she wanted to go home to the house she shared with Adrien.

“He’s my husband, Mom, Grandma. I know you think, but I don’t remember what I said. I was delirious. Adrien loves me.”

My heart broke watching her. She was 29 years old, smart, and kind, working as a marine biologist at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute.

She’d met Adrien at a fundraiser two years ago. He’d seemed different from his family, she said—more grounded, interested in her work, and not just the Carmichael name.

I’d been skeptical from the start. You don’t clean houses for rich families for four decades without learning that money changes people.

But Natalie was in love, and what could I say? I was just her grandmother, the one who still cleaned the Thornberry estate three days a week.

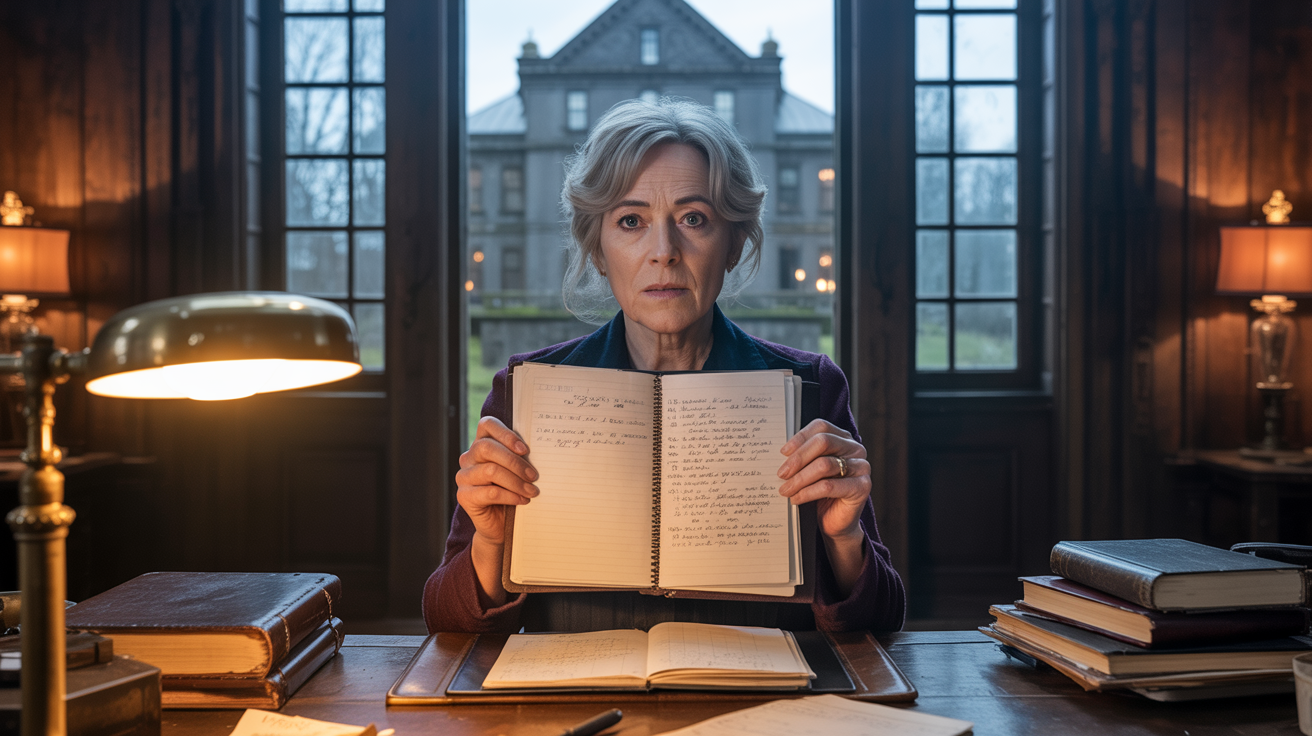

On the day Natalie was discharged, I went to see my older sister Helen. She’s 71 and lives in the same house we grew up in on Ocean Street.

Our mother died 10 years ago, but before she passed, she told us stories. These were stories about the families we worked for—things she’d seen and heard and quietly recorded in her journals.

Our mother understood that people who are invisible can be powerful if they’re patient. Helen opened the door in her gardening apron, soil on her hands.

“Dot, I heard about Natalie. How is she?”

“Alive. But Helen, I need to ask you something. Do you remember what Mama told us about the Carmichael family? About Richard’s father, Theodore?”

Helen’s face went still.

“The journals, where are they?”

“Attic. But Dot, you know what Mama said. Those secrets die with us unless there’s no other choice.”

“There’s no other choice now.”