After I Survived the Crash and Inherited $100M, My Husband’s New Wife Saw Me and Lost It

A Secret Life on Myrtle Street

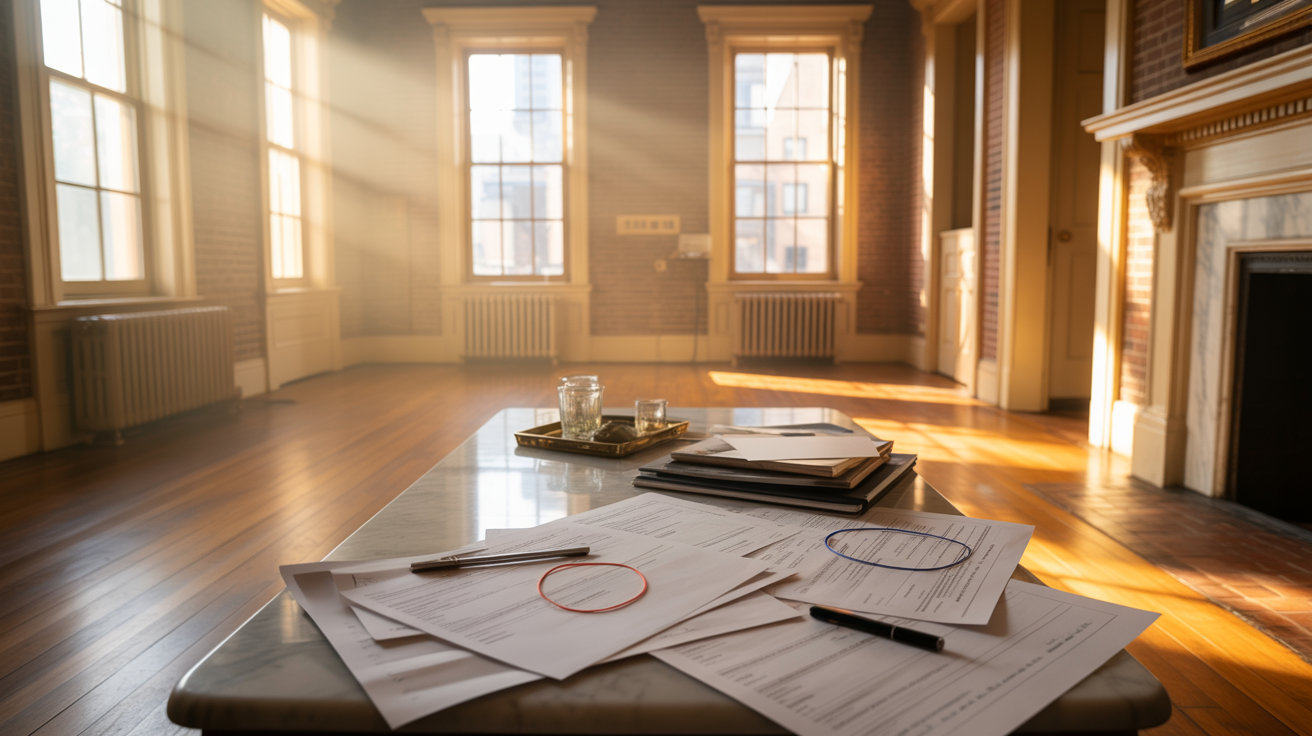

I will never forget the way the morning light slid across the brick of our Boston rowhouse and pulled on the oak floor like warm honey. The federal style windows cut skinny rectangles into the living room, and the radiator ticked as if it were counting my thoughts.

On the marble coffee table, a fan of contractor estimates dared me to say yes to a new kitchen. I had circled numbers and underlined phrases like custom shaker and quartz counters.

Daniel had pushed the papers away last night and said we could not afford to be ambitious. I kept the stack out anyway, the way you keep a door slightly open.

My name is Llaya Whitaker Brooks, and I live in the United States of America. Our house sits on Myrtle Street in Beacon Hill, a narrow lane with gas lamps, stubborn ivy, and stoops that invite neighbors to talk.

I bought the place at 29 after years of tuna sandwiches and second jobs. The mortgage was mine, the sweat was mine, and the vision was mine.

Daniel moved in later with tailored suits and a vintage road bike that he parked in the hallway like a sculpture. He liked to say he brought modern energy to my old house; I like to say the house had opinions of its own.

At 9:00, my attorney, Richard Hail, called from New York. Richard always sounds like a man who has read everything twice.

He cleared his throat and told me that my great aunt Margaret Whitaker had passed in Manhattan two weeks earlier and that probate had moved faster than anyone expected. She had left me $100 million.

The money sat in a trust I could open immediately. I pressed my palm to the banister I had stripped and varnished with my own hands, and the wood felt cool and steady.

The number hovered in the air like a bird that was either about to land or vanish. Aunt Margaret was the kind of New Yorker who knew the names of doormen and the hours of every museum.

When I was 12, she walked me through Central Park and made me promise to learn how money works so money would not get to tell me who I was. She never had children, but she had shelves full of first editions and a laugh that could cross a crowded room.

Standing in my Beacon Hill living room, I saw her apartment in my mind, the velvet sofa and the view of the river. I whispered, “Thank you.”

Even though no one could hear, gratitude came wrapped in shock. I had never held a number like that, not even in pretend.

I wanted to tell Daniel right away. I pictured us in the kitchen with the peeling cabinet doors and the slanted silverware drawer.

I would pop a cheap bottle of champagne and pour it into mismatched glasses. I would say we could repair the roof and replace the drafty windows without blinking.

I would say we could help his sister Renee in Chicago finish grad school without loans. I would say we could donate to the shelter in South Boston that always runs out of coats by January.

I would say in a voice I had not used in a long time that we were safe. I did not tell him that morning because I had a second call to make.

For the last year, through a rocky acquisition, I had stepped back from the daily grind at my company, Whitaker Ren. People like to call me a founder; the title on my internal email was chief executive officer.

Up close, that meant contract redlines at midnight, payroll at dawn, and a constant math problem about whose needs to meet first. I had returned two weeks earlier under my maiden name for a quiet transition.

We had a thousand people between Boston and New York. I could not know them all, but I tried to know the rhythm of our work.

That rhythm was my favorite sound. Daniel liked to call what I did consulting; he said titles were vanity and that real work does not need a crown.

I had let it slide, partly because I was tired and partly because it seemed easier to let him think the world was as tidy as he wished. Lately, I had been thinking about the day I would tell him the whole truth in one sitting.

I would tell him the scale of the acquisition, the scope of the team, and the way decisions stack up like dominoes and you learn to breathe while they fall. I thought about how I would tell him about Aunt Margaret, about the trust in New York, and about the quiet reality of a number that large.

I thought about the look on his face when he realized I had been carrying more than he knew. I decided to wait until the weekend.

It felt important to speak the words at our table with coffee and sunlight. I spent the late morning making a list of small errands: lemons for roast chicken, a new notebook for the next quarter’s plans, and a condolence card for Aunt Margaret’s oldest friend on the Upper West Side.

I tucked Richard’s follow-up email into a folder on the counter and told myself that patience is a form of care. The house hummed softly as if it agreed.

Around noon, I locked the front door and stepped into the brightness of Beacon Hill. Myrtle Street smelled like lilacs and bread from the corner bakery on Charles Street.

I thought about how a kitchen should smell on Sunday nights when the weeks are hard. I thought about paint colors and a farmhouse sink and a table with enough space to spread out contracts without moving the salt and pepper.

I turned toward Cambridge Street and waited at the crosswalk with a couple holding hands and a boy chasing a red ball on a string. The walk signal blinked green.

I remember the squeal of brakes before the sound of the crash. A delivery van ran the red light from my left, and the world tilted in a way that does not make sense even as it happens.

Metal buckled and glass burst into a thousand bright birds. The airbag hit me hard and the seat belt dug into my shoulder.

I tasted copper and felt the strange slow float of adrenaline moving through my limbs. My phone flew somewhere I could not see.

The folder with Richard’s email slid off the passenger seat and onto the floor mat, and I thought absurdly about paper cuts. Then there were voices.

Someone shouted to call for help. A siren rose and drew closer, and the noise braided itself with my heartbeat until I could not tell which was which.

I thought about the front steps on Myrtle Street and how the stone holds the day’s warmth long after sunset. I thought about Aunt Margaret’s velvet sofa and the way she had looked at me when she told me to learn money so money could not tell me who I was.