I Signed A “Safety Document” For My Daughter. She Used It To Secretly Put My Home On The Market And Move Me To Assisted Living. My Granddaughter Just Helped Me Lawyer Up. Now What?

The Counterattack

The next morning, I called my granddaughter Sophie. She was 24, finishing her master’s degree in social work at a university three states away. She called me Grandma Ellie, sent me poems she liked, and once drove nine hours just to bring me soup when I had the flu.

When she answered, I could hear the surprise in her voice.

“Grandma, is everything okay?”

“I need to ask you something, and I need you to be honest.”

A pause.

“Okay.”

“Has your mother said anything to you about moving me out of my house?”

The silence told me everything.

“She mentioned something,”

Sophie said carefully.

“Said she was worried about you being alone. That she found a really nice place with activities and medical staff.”

“Did she mention she’s already put the house on the market?”

Another pause. Longer this time.

“No, she didn’t mention that.”

“Sophie, I need your help.”

Sophie arrived that weekend with a duffel bag, her laptop, and a look on her face I recognized from her childhood whenever she was about to challenge something she thought was unfair.

“I made some calls,”

she said, setting her bag down.

“I talked to a lawyer friend from school. If you’re mentally competent, which you obviously are, the power of attorney doesn’t give Mom the right to sell your house. Not without your explicit consent.”

“She seems to think it does.”

“Then she’s wrong. Or she’s hoping you won’t fight it.”

I looked at my granddaughter, this young woman who had somehow become my ally in a battle I never expected to fight.

“I’m going to fight it.”

“Good,”

Sophie smiled.

“Because I already scheduled you an appointment with an elder law attorney. Monday at 10:00.”

We spent the weekend preparing. Sophie helped me gather documents, deeds, bank statements—anything that proved I was still the owner and manager of my own life. She took videos of me cooking, gardening, having perfectly coherent conversations about books and politics and the neighbors’ overly aggressive squirrel.

“Evidence,”

she said.

“In case anyone questions your capacity.”

I didn’t tell Patricia we were coming. I didn’t tell her anything.

Monday morning, I sat in the office of Helen Whitmore, attorney at law, and explained everything. She listened without interrupting, took notes, occasionally nodded. When I finished, she leaned back.

“Your daughter overstepped significantly. Can I stop the sale?”

“Absolutely. The POA you signed gives her authority to act on your behalf, but it doesn’t transfer ownership. She can’t sell property you own without a court declaring you incapacitated, which clearly hasn’t happened. So I just say no.”

“You say no loudly, legally, and with documentation.”

She pulled out a form.

“We’ll start by revoking the power of attorney. Then we’ll send a formal notice to the realtor and any interested buyers that the listing is unauthorized. If your daughter pushes back, we escalate.”

I signed the revocation that afternoon. The notice went out the next day. Helen also recommended I get a cognitive evaluation from my doctor just to have on record. I did. The results were unambiguous: Eleanor Chen, mentally competent, decision-making capacity intact.

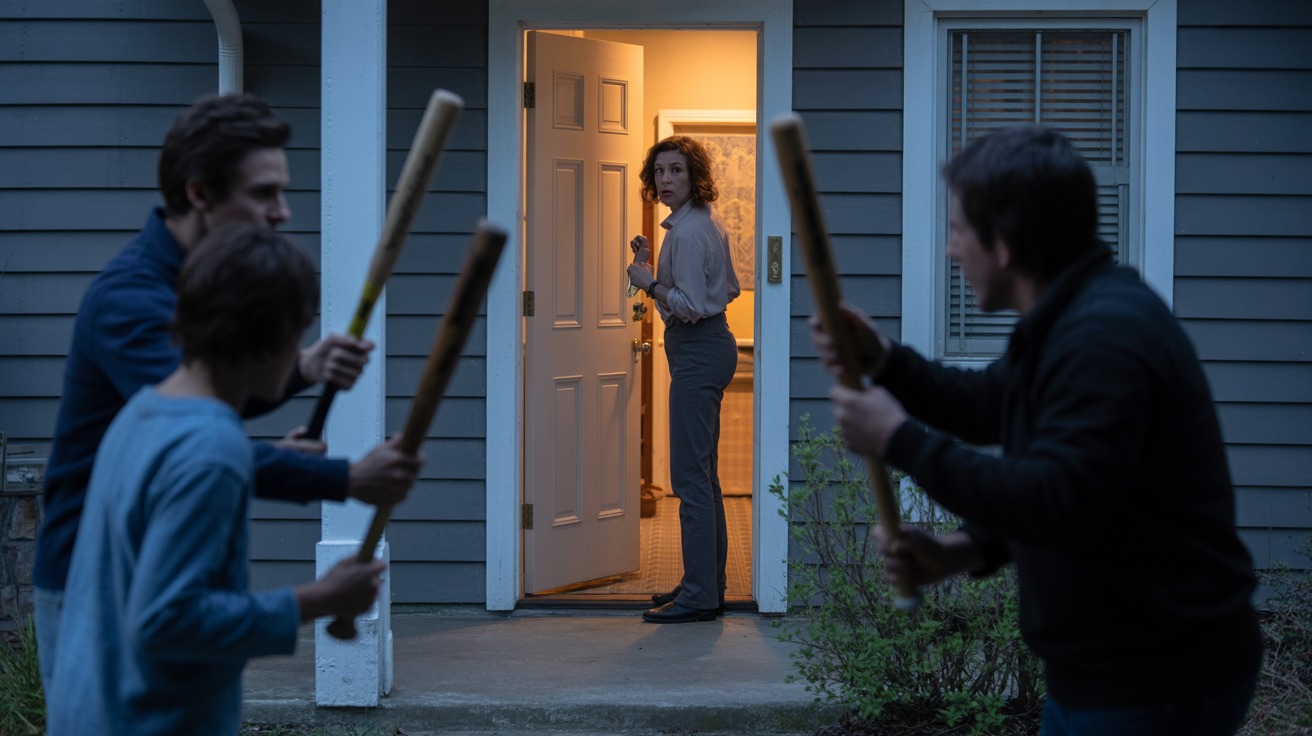

The Confrontation

Armed with paperwork, I went home and waited. Patricia called three days later, her voice sharp and unfamiliar.

“What did you do?”

“I protected myself.”

“You hired a lawyer against your own daughter?”

“Against someone trying to sell my home without my permission.”

“I was trying to help you.”

“No,”

I said quietly.

“You were trying to manage me. There’s a difference.”

She sputtered something about safety, about responsibility, about how I would regret this when I fell down the stairs and no one was there. I let her finish. Then I said:

“The listing has been removed. The POA has been revoked. If you want to be part of my life, you’ll need to treat me like a person, not a project.”

I hung up before she could respond.

The weeks that followed were strange. Patricia didn’t call, didn’t visit. Mark texted once to ask if I was okay; I sent back a thumbs up emoji and nothing else. Sophie called every few days, checking in, sending photos of her campus, of the cat she wasn’t supposed to have in her apartment.

I returned to my routines: library on Tuesdays, garden on weekends, coffee on the porch when the weather allowed. The house felt different now—not haunted, not sad, but awake somehow, like it had been holding its breath and finally exhaled.

I began to notice things I had stopped seeing. The way morning light hit the kitchen counter, the smell of the old books in George’s study, the particular creek of the third step that had announced his return from work for 20 years. I wasn’t just living in a house; I was living in a history.