My Daughter Was Suspended For Vandalism. When I Arrived, The Principal Froze: “chief Investigator?”

The Accusation and the Investigator’s Arrival

My daughter called from her school. “Mom, the principal is suspending me for vandalism I didn’t do, and they have a witness who says they saw me.”

When I walked into the office, the principal’s confident smile vanished and she stammered. “Chief investigator, I had no idea she was yours.”

The call came at 2:17 p.m. on a Thursday afternoon while I was reviewing surveillance footage from a charter school in the Northern District. My daughter Riley’s name flashed on my screen, and I almost didn’t answer because she knew I was working.

But something in my gut made me pick up. “Mom, you need to come to school right now.”

Her voice was shaking, that specific tremor that meant she was trying not to cry in public. “Principal Blackwell is suspending me for three weeks.” “She says I spray painted the gym walls last night and there’s a witness who saw me do it.” “But mom, I swear to God I didn’t do anything, I was home with you all night.”

I stood up so fast my chair rolled backward and hit the wall. “Riley, slow down. What witness? Who’s accusing you?”

“Madison Thorne.” Riley replied. “She says she saw me in the gym at 9:00 p.m. with spray paint cans, but I wasn’t there.” “Mom, you know I wasn’t there.”

“We watched that documentary about the college admission scandal together.” “Remember, we made popcorn?”

I remembered. We’d been on the couch until almost 11:00, and Riley had fallen asleep during the credits. I’d woken her up to go to bed around 11:30.

There was absolutely no way she’d been at school vandalizing anything. “Don’t say another word.” I said, already grabbing my jacket and badge. “Don’t sign anything.” “Don’t admit to anything.” “Don’t let them intimidate you.” “I’ll be there in 15 minutes.”

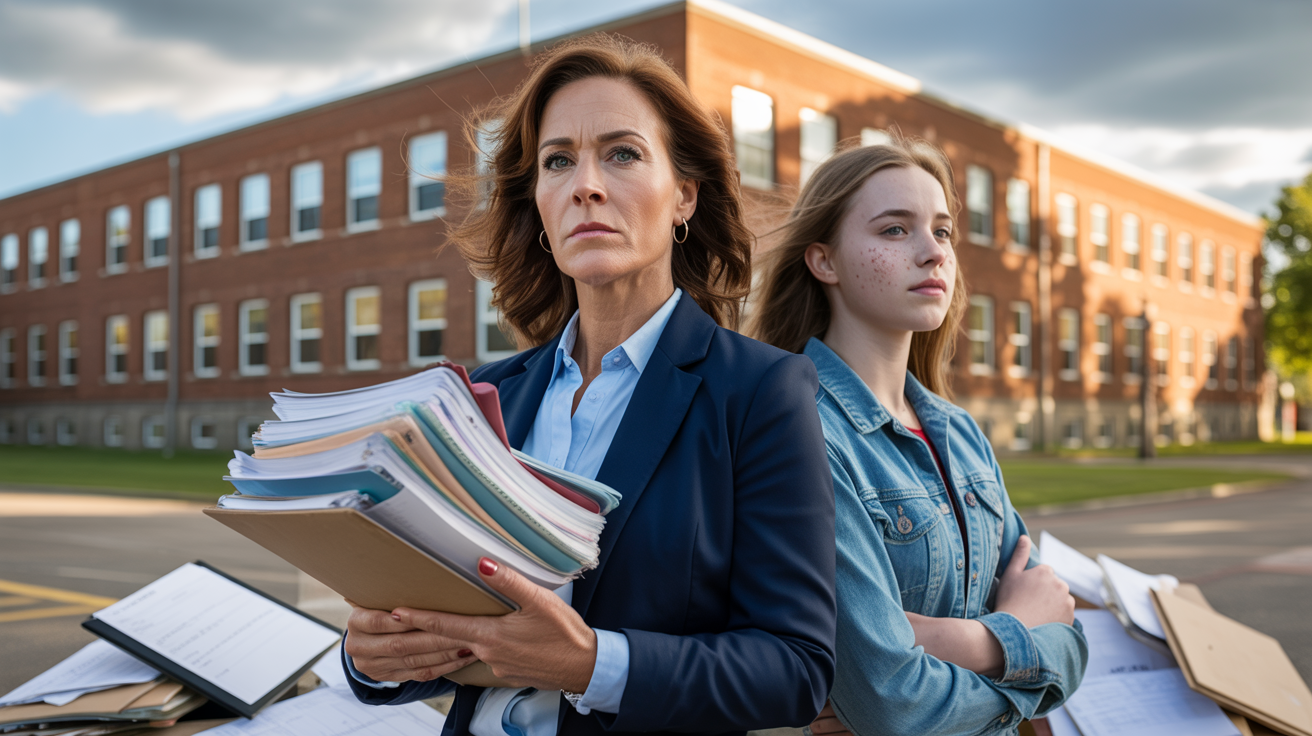

I’m Victoria Hayes, 41 years old, chief investigator for the State Department of Education’s fraud and compliance division. I’ve held this position for six years, investigating everything from embezzlement and bid rigging to falsified test scores and credential fraud.

Before that, I spent nine years as a forensic accountant with the FBI’s white collar crime unit. I know how to follow money, how to spot inconsistencies and documentation, and how to recognize when someone is lying to cover up something bigger.

My job has made me naturally suspicious of institutional authority, especially in schools where the power dynamics are so skewed and the oversight is often minimal. I’ve seen superintendents steal millions, principals manipulate enrollment numbers for funding, and teachers falsify grades to boost school ratings.

The education system, for all its noble intentions, is riddled with people who abuse their positions for personal gain. Riley knew what I did for a living.

She’d grown up listening to me talk about cases over dinner, understanding that accountability mattered and that telling the truth was non-negotiable. She was 16, a junior at Riverside Academy, honor roll every semester since sixth grade.

She was on the varsity soccer team, the debate team, and did volunteer work at the community food bank on weekends. She’d never been in trouble, never even had a detention.

The idea that she’d vandalize school property was absurd. But as I drove toward Riverside Academy, my hands tight on the steering wheel, I felt something nagging at the back of my mind.

Madison Thorne. That name was familiar, though I couldn’t immediately place why.

Riverside Academy was one of the top-ranked public high schools in the state, nestled in an affluent suburb with manicured lawns and a campus that looked more like a private college than a public school. The building was modern, all glass and steel, with a state-of-the-art athletic facility that had been completed two years ago at a cost of $18 million.

I’d actually reviewed the construction contracts as part of a routine audit when the project went over budget. But everything had checked out; no fraud, just the usual cost overruns that came with ambitious municipal projects.

I parked in the visitor lot and walked through the main entrance at 2:33 p.m. The administrative assistant at the front desk, a young woman named Clare who I’d met at a few school events, looked up with wide eyes.

“Miss Hayes, they’re waiting for you in the principal’s office. Riley’s already in there.” She said. I nodded and headed down the hallway, my heels clicking against the polished tile floor.

Through the glass walls of the main office, I could see Riley sitting in one of the chairs outside Principal Blackwell’s private office. Her face was blotchy from crying, her arms wrapped around herself.

When she saw me, relief flooded her expression. I pushed open the door and went straight to her. “Are you okay?”

She nodded, wiping at her eyes. “They won’t let me explain. They just keep saying Madison saw me and that’s all the proof they need.”

Before I could respond, the door to the principal’s office opened and Dr. Catherine Blackwell stepped out. She was 53, had been principal of Riverside for eight years, and had a reputation for running a tight ship.

She wore expensive suits and had her salt and pepper hair cut in a severe bob that made her look perpetually stern. She started to speak, her expression confident, almost smug.

“Miss Hayes, thank you for coming so quickly. I know this must be difficult, but we have a zero tolerance policy for vandalism.” And then she actually looked at me, and I watched the color drain from her face.

Her mouth opened and closed like a fish gasping for air. “Chief investigator Hayes,” She stammered, her previous confidence evaporating. “I, I had no idea Riley was your daughter.”

“She uses a different last name at school.” I said coldly. “My ex-husband’s name, Riley Cooper. But that doesn’t change the facts of this situation.”

“You’re accusing my daughter of vandalism based on what, exactly? The word of another student?” Dr. Blackwell recovered slightly, straightening her shoulders.

“We have a credible witness, Miss Hayes. Madison Thorne is a trustworthy student, a senior member of student council.” “She has no reason to lie.”

“She reported seeing Riley in the gymnasium last night at approximately 9:00 p.m. with several cans of spray paint.” “This morning we discovered extensive vandalism in the gym: profane language, offensive imagery, damage that will cost thousands of dollars to repair.”

“And you’ve confirmed Riley was actually at school last night? You’ve reviewed security footage?” I asked. Dr. Blackwell hesitated.

“The security system in the gymnasium has been experiencing technical difficulties. The cameras weren’t recording last night.” “How convenient,” I said. “So you have no physical evidence, no video footage, just the accusation of one student against another.”

“And based solely on that, you’re suspending my daughter for three weeks?” “Madison is very reliable,” Dr. Blackwell said defensively.