My Father Signed Papers Saying I Wasn’t His Son. I Used Them When He Sued Me For Support Now He Is..

A Ghost from the Past

A Ghost from the Past

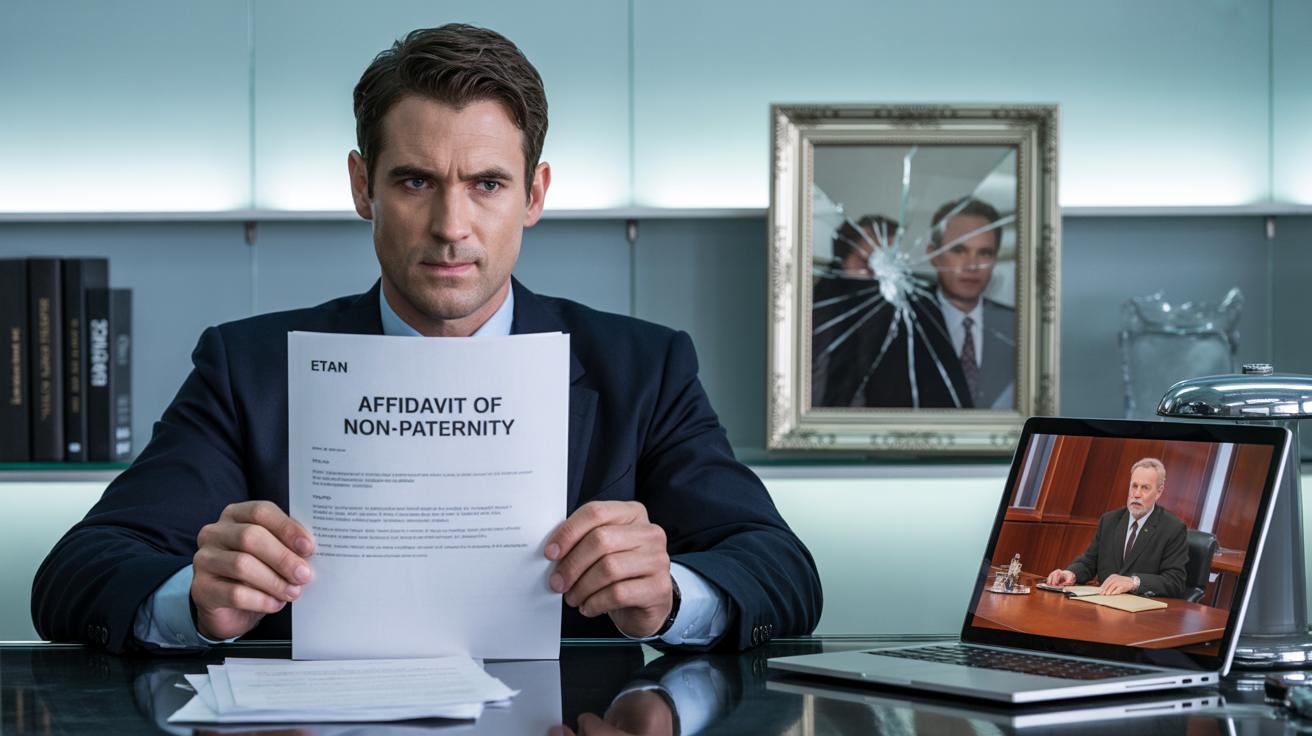

My father signed papers saying I wasn’t his son. I used them when he sued me for support, and now he is begging.

My father spent $40,000 on high-powered attorneys to legally prove I was illegitimate so he could cut me out of my grandfather’s trust. Ten years later, he sued me for $3,500 a month in support because he was my dad.

My name is Ethan. I’m 34 years old, a biotech researcher living in Boston, and until last month, I thought the file on my childhood was closed.

I thought the ink was dry and the wounds had scarred over enough that I could forget about them. I was wrong.

The past doesn’t die; it just waits for you to make enough money to be worth haunting. I was sitting in my lab waiting for a centrifuge to spin down when security called up to my floor.

There was a process server in the lobby asking for me by name. I figured it was a subpoena related to some patent dispute or another.

That’s a hazard of the trade when you work in biotech. Pharmaceutical companies are always suing each other over intellectual property, and sometimes the researchers get dragged into it as witnesses.

But when I walked down to the lobby and opened the thick manila envelope, I didn’t see corporate letterhead. I didn’t see anything related to patents or research or any of the professional complications I’d grown accustomed to handling.

I saw the seal of the Connecticut Superior Court. My father, Gerald, a man who had publicly and legally disowned me when I was 24 years old, was filing a petition under the state’s filial responsibility statutes.

He was claiming indigence. He cited a string of failed venture capital investments, deteriorating health, and mounting medical bills.

He was demanding that I, his biological son, pay for his assisted living facility and provide a monthly stipend to cover his expenses. To understand the sheer unadulterated audacity of this lawsuit, you have to understand our history.

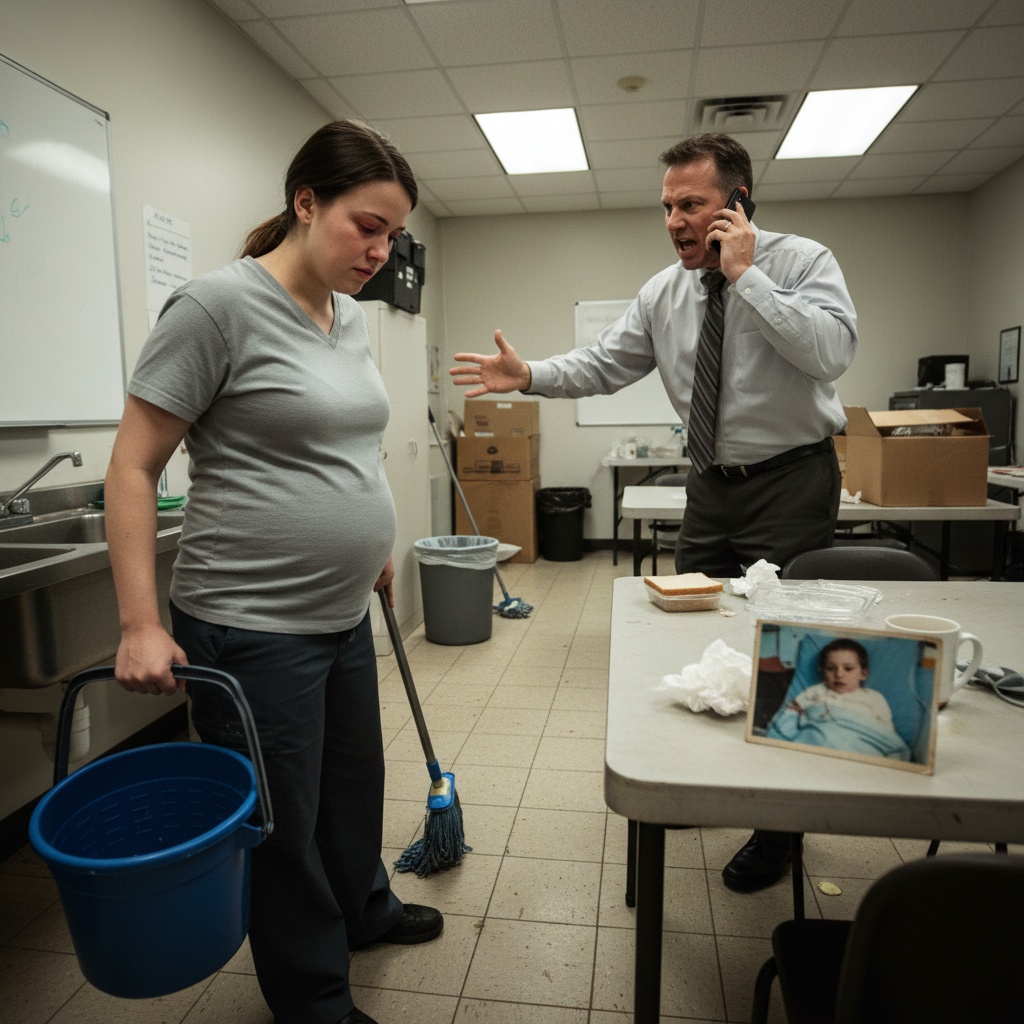

You have to understand who Gerald really was. Gerald wasn’t a father; he was a portfolio manager, and I was just an underperforming asset in his ledger.

I grew up in Darien, Connecticut, in a house that felt less like a home and more like a museum where I was the only clumsy tourist. Everything was pristine, everything was expensive, and everything was meant to impress visitors, not to make a child feel comfortable or loved.

The furniture was the kind you weren’t supposed to sit on. The artwork was the kind you weren’t supposed to touch.

My father was the kind of man you weren’t supposed to disappoint. My mother died when I was six from cancer.

It happened fast enough that I barely had time to understand what was happening before she was gone. One month she was reading me bedtime stories and making me hot chocolate on cold mornings; the next month I was wearing a tiny black suit at her funeral.

I was confused about why everyone was crying and why my mother was sleeping in a box that they were putting in the ground. I remember the day they told me she wasn’t coming home from the hospital.

Gerald sat me down in his study, the same room where he would later blackmail me out of my inheritance, and explained death to me like he was explaining a business transaction. It was matter-of-fact and clinical; there was no warmth, no comfort, just information delivered, and then we moved on.

I cried for weeks. I cried at night when no one could hear me, I cried in school bathrooms between classes, and I cried every time I saw something that reminded me of her.

Everything reminded me of her. Gerald’s response to my grief was impatience.

He told me to pull myself together.

“He said that crying wouldn’t bring her back and that I needed to start acting like a man,”

even though I was six years old and had just lost the only person who had ever made me feel safe.

After that, it was just me and Gerald, a six-year-old boy and a man who treated parenting like dog breeding. Gerald was obsessed with legacy, bloodlines, and good stock.

He talked about family the way some people talk about racehorses—genetics and breeding and potential. If I got a B on a report card, I was defective.

If I didn’t make varsity, I was a poor investment. If I showed any weakness or vulnerability or normal childhood emotion, he looked at me like I was a product that had arrived damaged from the factory.

I learned early to hide my feelings around him. I learned to perform competence whether I felt it or not.

I learned that love in our house was conditional and that the conditions were never clearly stated but always ruthlessly enforced. But the real fracture in our relationship didn’t happen until I was 24.

That’s when my grandfather died, and the truth about my father came into focus like a photograph developing in a dark room. My grandfather on my father’s side was a steel magnate with old money, the kind of wealth that builds libraries and names hospital wings.

He was a complicated man with a heavy conscience about how that wealth had been accumulated. He spent his later years trying to do some good with it through philanthropy, charitable trusts, and anonymous donations to causes he believed in.

He was also the only source of genuine warmth in my childhood. When Gerald was cold and distant, grandfather was the one who took me fishing.

When Gerald criticized everything I did, grandfather was the one who told me he was proud of me. When Gerald made me feel like a disappointment, grandfather made me feel like I mattered.

Before he died, grandfather set up what’s called a generation-skipping trust. It’s a legal structure designed to pass wealth directly to grandchildren while bypassing the middle generation.

Partly it’s for tax purposes, avoiding estate taxes by skipping a generation. But partly, I think grandfather did it because he knew exactly who his son was.

He knew Gerald would burn through any money that came to him and leave nothing for the future. The trust was substantial, multiple millions, and it was designated specifically for me.

Gerald was furious when he found out—absolutely livid. He had spent his entire adult life waiting for his father to die so he could inherit the family fortune.

He had structured his finances around that expectation. He had made promises to people based on money he assumed would be his.

Then the old man had the audacity to skip right over him and hand everything to his grandson. I was 24, fresh out of grad school, and still grieving the loss of the only person in my family who had ever made me feel loved.