My Husband Blamed My “Bad Genes” For Our Son’s Death Seven Years Ago. He Divorced Me And Used The Insurance Money To Get Rich. Now, The Hospital Just Called With The Real Lab Results. What Do I Do?

They couldn’t prove he knew about the murder beforehand, but his actions afterward, his cruel treatment of me, his profiting from Noah’s death—all of it painted a picture of complicity if not direct involvement.

The trial date was set for six months out. Six months to prepare, to face them in court, and to tell Noah’s real story.

I would finally assign blame where it belonged: not on my genes, not on my unknown biological history, but on a woman so obsessed with perfection that she’d murdered her own grandson to preserve an illusion.

That night I called my sister Camille.

“I need to tell you something about Noah,” I said when she answered.

“Bth, what’s wrong?”

“He didn’t die from my genes. He was murdered, and I need my family back.”

The silence stretched across the phone line. Then Camille was crying, saying my name over and over, apologizing for seven years of distance, seven years of fear, and seven years of believing a lie that had destroyed more than just me.

The courtroom was packed the day of sentencing. Six months of testimony, evidence, and revelations had led to this moment.

Vera stood in her prison jumpsuit, a far cry from her usual St. John suits, as the judge read the verdict. Guilty of first-degree murder. Sentenced to life without parole.

She was 71 years old; she would die in prison. Devon received 25 years for conspiracy and insurance fraud.

The prosecution had found emails between him and his mother from the week after Noah’s death discussing the insurance payout and how to manage the narrative around my genetic culpability. He might not have known about the murder beforehand, but he’d enthusiastically participated in destroying me afterward.

“Does the victim’s mother wish to make a statement?” the judge asked.

I stood, my legs steady for the first time in seven years. Camille sat in the front row with my mother, both of them crying silently.

Behind them sat Patricia from the bookstore, Dr. Reeves who’d uncovered the truth, and surprisingly, Devon’s new wife Melissa. She had filed for divorce the day after his arrest and brought their twin boys to meet me, saying they deserve to know about their brother.

“Your Honor,” I began, my voice carrying through the silent courtroom. “For seven years I believed I killed my son with defective genes. I lost everything: my marriage, my home, my career, my family’s trust, and most importantly, my right to grieve Noah properly.”

“While I was tormented by guilt, his killer attended charity galas and posted Facebook photos with her new grandchildren. She watched me fall apart and felt nothing but satisfaction that her plan had worked.”

I turned to face Vera directly.

“You killed Noah because you couldn’t accept that your precious Hartwell bloodline carried Huntington’s disease. But here’s what you never understood: Noah was perfect not because of his genes, but because he was loved. In his three weeks of life, he knew nothing but love. That’s the only legacy that matters.”

Vera’s expression never changed—rigid and cold to the end. But Devon was sobbing, the reality of what he’d lost and what he’d done finally breaking through his denial.

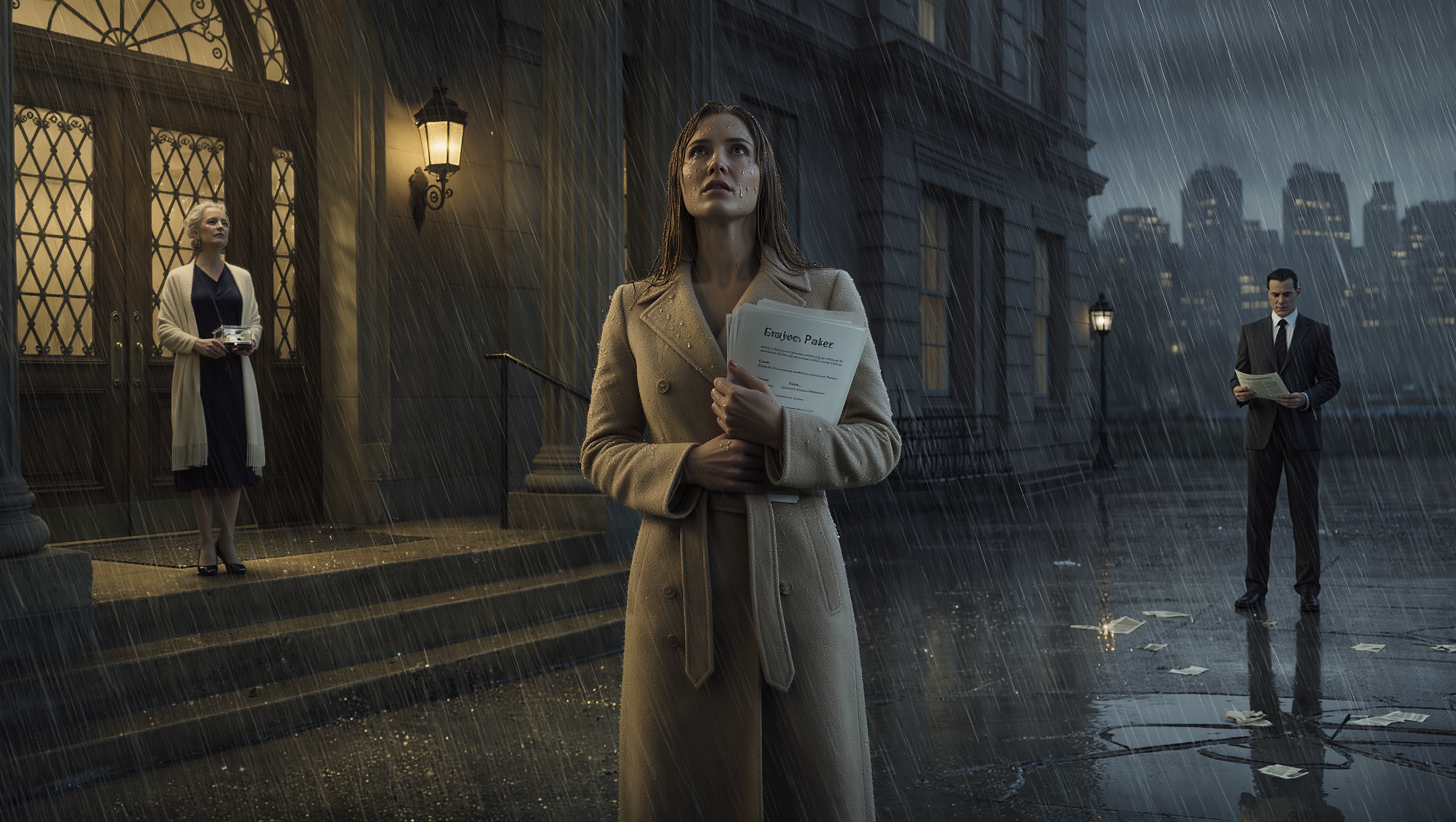

After the sentencing, I stood outside the courthouse with Camille and my mother, breathing free air that didn’t taste like guilt for the first time since Noah died. Reporters pushed forward with questions, but I only answered one.

“What do you want people to know about your story?”

I looked directly at the camera.

“That mother’s intuition is real. I knew something was wrong with the story of Noah’s death, but I let people with louder voices and fancier degrees convince me to doubt myself. If something feels wrong, keep pushing for answers. The truth might be horrible, but it’s better than living with a lie.”

The settlement from the hospital’s insurance and the civil suit against the Hartwell estate came to $3 million. I donated a third to the Innocence Project because I knew what it felt like to be wrongly blamed.

Another third went to creating the Noah Hartwell Foundation for genetic testing and counseling for families who actually needed it. These were families dealing with real genetic conditions, not manufactured ones.

With the final third, I bought a small house in Oak Park with a garden where I planted roses that bloomed every spring around Noah’s birthday. I returned to working with children, but now as a grief counselor for parents who’d lost infants.

I told them what I wished someone had told me: sometimes tragedy isn’t random, sometimes it isn’t your fault, and healing comes from truth, even when that truth is more horrible than the lie.

Dr. Monica Ree, my therapist, asked me during our last session how I felt about forgiveness.

“I don’t forgive Vera,” I said honestly. “Some acts are unforgivable. She murdered a baby to protect her pride. But I forgave myself, and that’s what matters.”

I kept one photo on my mantle. It was Noah at three days old, perfect and loved. Underneath, a small plaque read: “Noah Hartwell. Three weeks of life. A lifetime of love. Your truth freed mommy”.

Devon wrote me once from prison, a long rambling letter about his sorrow and his shock about his Huntington’s diagnosis. He wanted absolution I couldn’t give him.

He’d spent seven years telling everyone I’d killed our son with defective genes while building his fortune on Noah’s grave. His tears at the trial didn’t erase the cruelty of his abandonment.

But his twin boys, Thomas and Andrew, visit me once a month. Melissa brings them, and we look at photos of Noah together.

They know they had a big brother who died. When they’re older, I’ll tell them the full truth, not to hurt them, but to arm them against anyone who would tell them their worth is in their genes rather than their hearts.

The last time I visited Noah’s grave, I brought him a letter I’d written about everything that had happened. I read it aloud to his headstone, then burned it there in the cemetery, watching seven years of lies turn to ash and drift away on the wind.

“You were never broken, baby,” I whispered to the stone. “And neither was I.”

Some stories don’t get happy endings, but sometimes they get just endings, and that has to be enough. Noah couldn’t be brought back, but his truth could be told.

His murder could be punished, and his mother could finally grieve him properly without the weight of false guilt. That’s the thing about truth—it doesn’t always heal, but it does set you free.

After seven years of prison built from lies, freedom felt like breathing again. It felt like spring after the longest winter, like coming home to myself at last.

I think Noah would want me to be free. I think he’d want me to know that love is stronger than genetics, that truth is stronger than lies, and that a mother’s love survives even the cruelest deceptions.

His three weeks of life mattered not because of his genes, but because he was here. He was loved, and his story—his real story—deserved to be told.