My Husband’s Driver Warned Me Not To Get In The Car. I Followed Him To A Secret House And Found Him Playing ‘daddy’ With Another Woman. How Do I Take Him Down?

The Bus to Oakridge

In the morning, Carol lied. It was the first lie in 20 years of marriage, and it came with an unexpected ease, as if her tongue found the words on its own.

“Ashley isn’t feeling well. She has a terrible stomach ache. I’ll stay home for now. I’ll call the doctor, and then I’ll make my own way in.”

Art, already in the hallway with his keys in hand, didn’t even glance toward their daughter’s room. He just nodded, blew a kiss in the air near Carol’s ear, and walked out the door, muttering something about being late.

Carol waited until the sound of the engine faded, and only then did she put on her coat. Her hands were shaking so badly that she couldn’t get her arm into the sleeve on the first try.

The bus station greeted her with the smell of exhaust fumes and fried donuts. The bus to Oakridge, an old rattling vehicle, was already at the bay, wheezing smoke. Carol got on, trying not to look up, and sat in the very back by the window.

She felt as if everyone knew why she was there, as if it were written on her forehead: Wife spying on her husband.

The bus was half empty: a few retirees with empty shopping baskets, a student with headphones, and a woman with a girl of about seven sitting two rows ahead. The bus lurched forward, swaying heavily over potholes. Carol stared out the window at the gray apartment buildings rushing by, but she didn’t see them. Walter’s words echoed in her head: “Go watch.”

The little girl in front began to fidget, knelt on her seat, and looked back directly at Carol. Carol froze. Her heart skipped a beat, then another, and began to pound in her throat, making it hard to breathe.

The girl had Art’s eyes. The same almond shape, the same slightly drooping outer corner that gave his gaze an eternal, touching sadness, and a chin with a tiny dimple that Carol had kissed so many times on her husband. The girl looked at her with childish curiosity, twisting a lock of blonde hair around her finger exactly the way Art did when he was nervous or thinking.

But it wasn’t the face that held Carol’s gaze. On the girl’s neck, over her pink jacket, hung an antique silver locket in the shape of an oval shell.

Carol remembered that locket. She had found it in the pocket of Art’s jacket about 6 months ago.

“It’s a gift for mom’s anniversary,” he had said then, quickly putting the piece of jewelry away. “I took it to get fixed. The clasp was broken.”

And then they lost it at the shop.

“Can you believe it? I raised hell. But what good did it do?”

Carol had comforted him then, saying it was the thought that counted. Now, that lost locket was shining on the neck of a strange little girl with her husband’s eyes.

Carol gripped the bar of the seat in front of her so hard her knuckles turned white. The air in the bus became unbearably thin. She wanted to scream, to stop the bus, to run, but she sat there paralyzed by the horror of recognition.

“Lily, sit down properly,” the woman beside her chided.

She was young, pretty, with a stylish haircut. Victoria. The name surfaced in her memory on its own. Out of nowhere. She didn’t know her name, but for some reason, it fit this well-groomed woman in a fashionable coat.

The Other Life

The bus pulled into Oakridge. The woman and the girl stood up and moved toward the exit. Carol, as if in a dream, got up after them. Her legs felt like they were made of cotton, not her own.

They got off at a stop in a neighborhood of nice houses. Carol kept her distance, hiding behind the few passersby and lampposts. She felt like a thief, a criminal stalking someone else’s happiness, but there was nothing left to steal. Her own happiness was turning to dust with every step.

The woman and the girl turned down a side street lined with neat brick houses. Parked next to one of them, with a green fence and a well-tended front yard, was a familiar car. Art’s silver sedan.

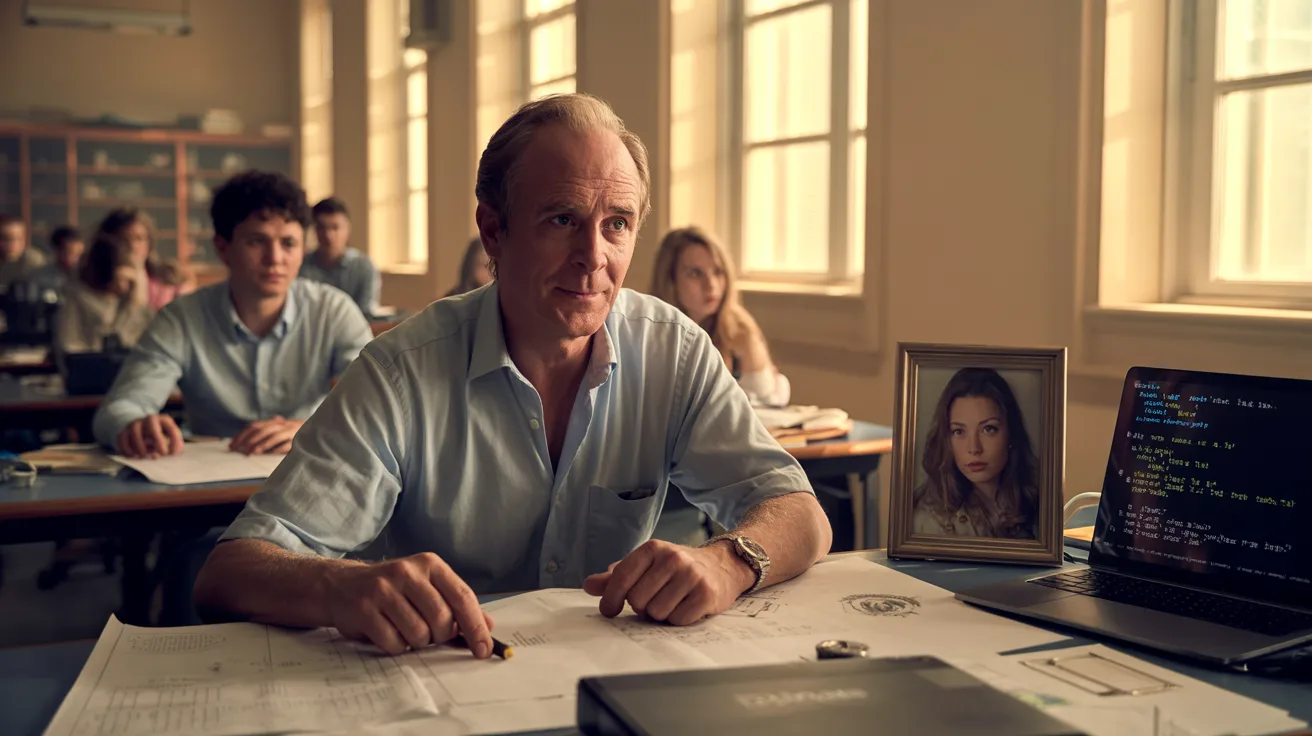

Carol stopped at the corner of the next house, pressing her back against the cold brick wall. She peeked out just enough to see the front door. The gate opened. Art stepped out onto the porch. He was wearing a casual sweater, the same one with the reindeer that Carol had given him last Christmas, and which, according to him, he had forgotten in a locker at work. In his hands, he held a large mug of steaming tea.

“Daddy, Daddy’s here!” the little girl shrieked, dropping her backpack and running to him.

Art set the mug down on the railing, opened his arms, and caught the girl. He lifted her into the air, spinning her around, laughing. Carol hadn’t heard him laugh like that in years. Genuine, loud, young.

“My princess, how was the trip?” he kissed the top of the girl’s head, then sat her down and walked over to the woman.

He wrapped his arm around her waist with a possessive, familiar gesture. The woman said something to him, smiling, and adjusted the collar of his sweater. Art leaned in and kissed her. Not on the cheek, the way he had kissed Carol that morning—on the lips, long and tenderly.

Carol slid down the wall. Her legs refused to hold her. She sat right on the damp, dirty asphalt, not caring about her coat.

This wasn’t an affair, not a casual fling on a business trip. This was a life. Another life. A real, full life where Art was happy and at ease. A life where he was a father to a little girl with his eyes. A life where there was no place for Carol. And judging by the girl’s age, there hadn’t been for about seven years.

Something inside her chest snapped like a taut string that had been holding her together all these years. Carol covered her mouth with her hand to keep from sobbing out loud. Her shoulders shook with silent crying. Tears streamed down her cheeks—hot, salty, smudging her mascara, dripping onto the gray collar of her coat.

She sat on the ground, a small, crushed woman, watching the idyllic scene behind the green fence through a veil of tears. She remembered how she had scrimped on groceries to buy Art good shoes, how she had mended his socks, how she had believed every word about meetings and business trips. How foolish she had been. How blind. How pathetic.

Art picked up the girl’s backpack from the ground, put his other arm around his wife, and the three of them went into the house. The door closed, shutting Carol out from their warmth.

She was left alone in a strange town, on the dirty asphalt, with a hole in her chest the size of that house. She tried to breathe, but the air caught in her throat like a thorny knot. She curled up, hugging her knees, burying her face in the damp wool of her coat. Finally, she let herself cry aloud, quietly whimpering like a beaten dog that had been thrown out into the cold.

Carol didn’t get up from the ground right away. First, she braced herself with a palm against the rough brick. Then slowly, like an old woman, she straightened her back. Her knees were wet and dirty. But it didn’t matter. She brushed off her coat with a mechanical, meaningless gesture and walked away from the house with the green fence.