My Mother Threw The First Stone At My Execution While My Brother Watched In Silence. I Was Rescued By A Resistance Group That Proved The Death Lottery Is Rigged To Steal Our Land. What Do I Do Now That I’ve Returned To Make The Council Draw Their Own Names?

More pain is shooting through my already broken ribs. Hands grab me from behind and I feel a knife sawing through the ropes on my wrists.

The rope falls away and my arms drop, shoulders screaming from being held back so long. Someone throws me over their shoulder like a bag of flour and starts running before I can even process what’s happening.

I’m bouncing against their back with every step, my ribs grinding together and making me want to scream. The guards are yelling somewhere behind us and the crowd is panicking in the smoke.

People are running into each other and coughing. Gunshots crack through the air, loud pops that make my ears ring worse.

My rescuer doesn’t slow down at all, just keeps running while I hang over their shoulder too hurt and confused to fight or help.

More gunshots and someone screams, but we’re moving away from it all. The smoke is getting thinner as we go.

I can feel my rescuer’s breathing hard and fast against my stomach where I’m draped over them. Blood from my head wound drips down onto their back leaving a trail.

We run through narrow alleys between buildings. My rescuer’s boots hit the ground hard with each step.

They’re breathing really hard now but never slowing down even though I must weigh a lot. The smoke and chaos fade behind us as we get farther from the square.

The yelling and gunshots are getting quieter. We reach the edge of the community where the buildings look old and falling apart, places I’ve never been allowed to go.

The council always said these buildings were unsafe and might collapse, that we had to stay away from this whole section.

But my rescuer runs right into this forbidden area without hesitating, taking turns through alleys like they know exactly where they’re going.

The buildings here have broken windows and doors hanging off hinges, some with roofs caved in. Weeds grow up through cracks in the road and everything looks abandoned.

I try to lift my head to see where we’re going, but the movement makes my vision swim and my stomach lurch.

My rescuer carries me into a big warehouse with rusted metal walls and a roof full of holes. They don’t stop at the main floor, instead heading straight for a door in the back corner.

We go downstairs into a basement I didn’t know existed, the air getting cooler and damper as we descend.

At the bottom there’s a large room lit by battery-powered lanterns, and six other people wait there with boxes of medical supplies and weapons laid out on tables.

A woman with short dark hair steps forward and my rescuer carefully transfers me from their shoulder to her arms. She lays me down on a makeshift bed, really just blankets over a thin mattress on the floor.

My whole body is screaming with pain. Every movement is making something hurt worse.

The woman starts checking my injuries right away, her hands gentle but firm as she looks at my head wound.

I’m trying to process that I’m somehow still alive, that these people saved me from the execution, that I’m not dead in the square with stones piled on top of me.

The woman with dark hair looks into my eyes and introduces herself as Audrey.

She explains in a calm voice that they’re part of a resistance movement that’s been operating in secret for two years.

“They’ve been watching the lottery and waiting for the right moment to act,” she says.

She tells me they chose to save me because I’m young enough to recover but old enough to fight back.

She also says my father’s execution three months ago was so obviously manipulated that it proved the council’s corruption to anyone paying attention.

Her voice is steady and sure like she’s thought about this a lot. She explains they’ve been documenting the lottery patterns and building evidence, waiting for a rescue opportunity that would expose the system.

Saving someone mid-execution and having them survive to tell about it is powerful proof that the lottery isn’t sacred or necessary.

I’m having trouble focusing on her words because my head is pounding and my ribs feel like they’re stabbing into my lungs with every breath.

I managed to ask about my mother and brother through split lips that hurt to move.

“Are they in danger now because of my rescue?”

Audrey’s face goes serious and grim.

“The council will definitely punish your family as an example to stop other people from trying to help resistance members,” she explains. “They’ll probably select one of them for next month’s lottery.”

She says, “But bringing them here now would lead the guards straight to this hideout and get everyone killed.”

She says it quiet and gentle but honest, not trying to make it sound better than it is.

The resistance has 15 members total and this basement is their main base, so protecting this location matters more than individual rescues right now.

I feel sick hearing that my family is in danger because these people saved me. But I also understand the logic.

If the guards find this place everyone here dies and the resistance ends. Audrey puts her hand on my arm, carefully avoiding the bruises, and tells me they’re working on a plan to protect my family, but it’ll take time.

The Cost of the Truth

A younger woman with light brown hair comes over with clean cloths and bandages. She introduces herself as Liz and starts cleaning my wounds, wiping blood off my face with gentle touches.

She explains she was training to be a nurse before her sister got selected two years ago, so she knows how to treat injuries.

The pain is incredible as she cleans the cut on my head, worse than when the stone first hit. I forced myself to stay quiet though, biting my lip hard enough to taste more blood.

Liz wraps my ribs tight with long strips of cloth, each wrap making it a little easier to breathe even though it hurts like crazy.

She tells me I probably have two or three cracked ribs but they should heal okay if I don’t move around too much.

I watch the other resistance members moving around the basement with smooth efficient movements like they’ve done this before.

They’re checking weapons, organizing supplies, talking in low voices about something I can’t hear.

One man is cleaning the smoke bomb equipment in the corner. A woman is writing notes in a journal.

Everyone moves with purpose, no wasted motion. Liz finishes wrapping my ribs and moves to checking my arms and legs for breaks, her hands pressing carefully on bones to see if anything shifts wrong.

The whole time I’m thinking about my mother and brother back in the square, wondering if they think I’m dead, wondering what the council will do to them.

Over the next few hours resistance members come over one by one to introduce themselves and share their stories.

A man named Wyatt tells me his wife was selected two years ago right after she spoke against the council at a community meeting.

A younger woman explains her brother got chosen three months after their family refused to sell their farm to a council member.

Everyone here lost someone to the lottery and everyone noticed the same patterns I did about council families never getting selected.

Audrey sits with me while people talk and eventually tells me about her own parents.

Her mother questioned a council decision at a meeting five years ago and got selected the next month.

Her father spoke up about the suspicious timing and got chosen six months later.

Audrey was 17 when it happened and she’s been building this resistance ever since, collecting evidence and waiting for the right moment to act.

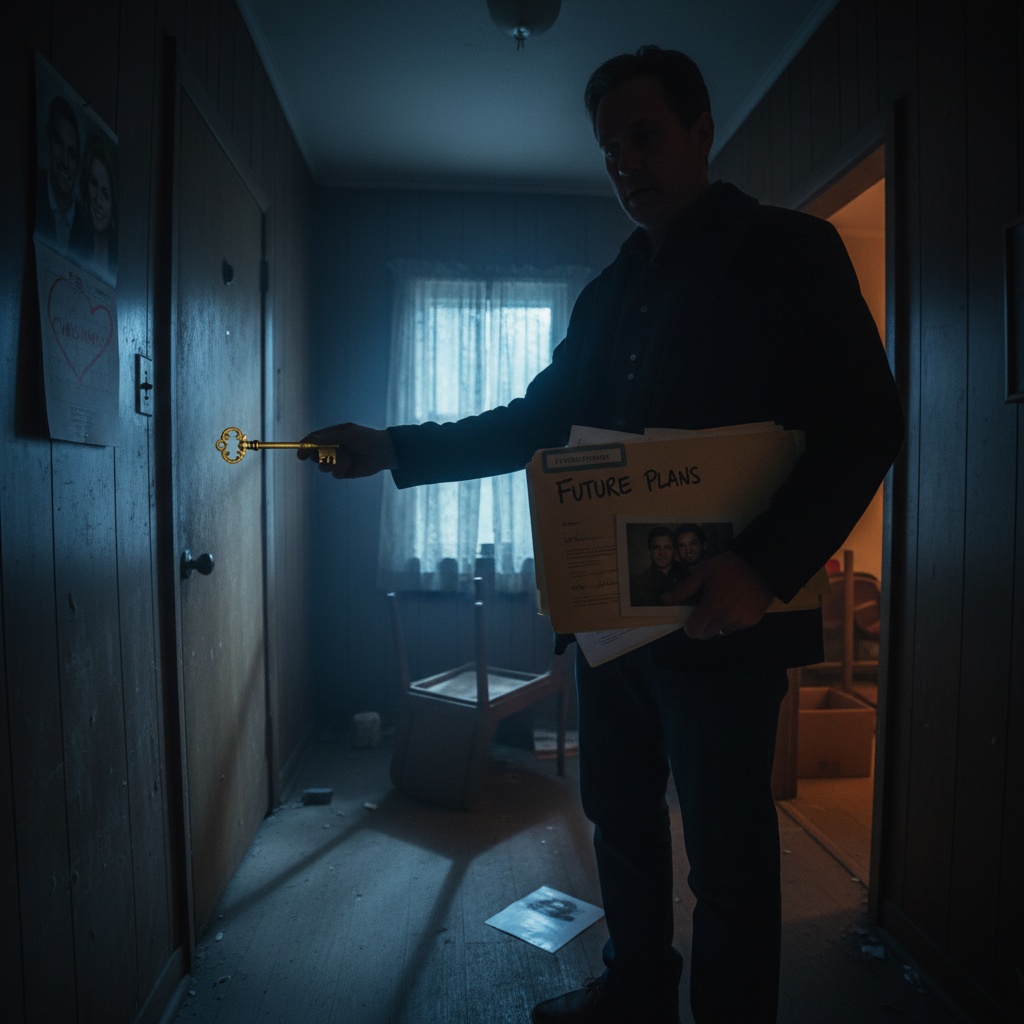

She pulls me up carefully, supporting my weight because my ribs still hurt badly, and walks me across the basement to a wall covered in papers.

Names and dates fill every inch of space, lines connecting families to council members, notes about property and disputes and public disagreements.

I read through the names and recognized most of them, people I watched die in the square over the years.

Every single person either opposed the council somehow, or owned something the council wanted, or belonged to families that threatened council power.

The pattern is so clear now that I see it laid out like this. So obvious that I feel stupid for not putting it together sooner.

Audrey points to specific clusters of names, showing how the lottery targeted entire families sometimes wiping out anyone who might continue resistance.

She shows me documents they stole from council offices proving property transfers right after executions, proving the lottery was never about population control at all.

A girl about my age comes over carrying a plate with bread and a cup of water.

She introduces herself as Kaye, Audrey’s younger sister, and sets the food down beside me.

I try to eat but my stomach feels twisted and wrong, though I force down a few bites because Liz said I need to keep my strength up.