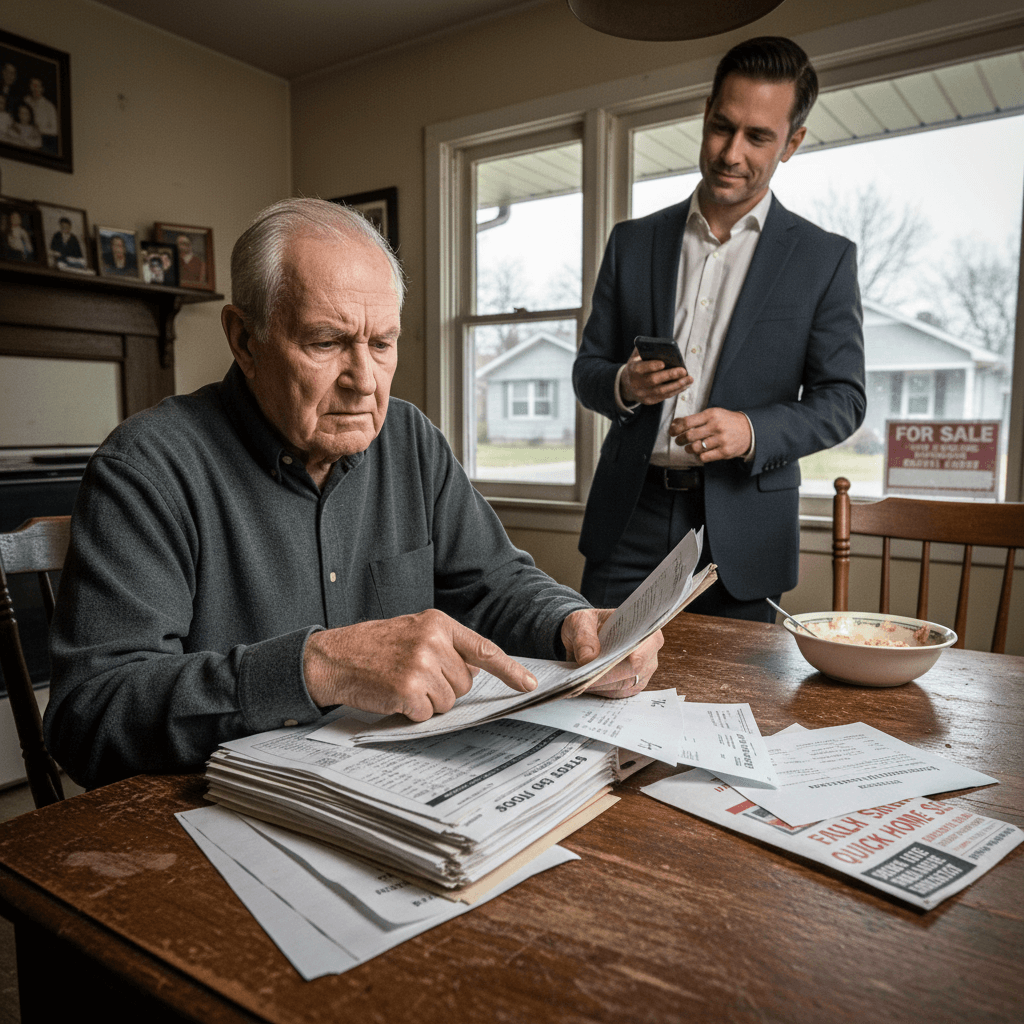

My Son Is An Attorney Who Stole My $5.8m Life Savings And Made Me Homeless. He Told The World I Was Senile To Cover His Gambling Debts. How Do I Recover When My Own Child Leaves Me For Dead?

“Pearl, he did this to himself.”

“I know. But he’s still my dad.” She wiped her eyes.

“I hate what he did to you. I’ll testify against him in court, but I still, I still love him. Is that wrong?”

“No, sweetheart. It’s not wrong.”

She looked at me.

“Do you still love him?”

I thought about that for a long time.

“I love who he was, who I thought he was. I don’t know if I love who he is now, but I want to believe he can be better.”

The trial lasted three weeks. Linda presented our evidence methodically: the gambling debts, the forged documents, the systematic theft.

Rachel had signed papers claiming I was mentally incapacitated when she’d notarized the power of attorney, even though I’d been perfectly lucid. That was notary fraud, a crime that would cost her CPA license.

Jeremy’s attorneys argued he’d been acting in my best interest, making investment decisions he thought were sound. But the jury didn’t buy it.

You can’t invest money in slot machines. On the 15th of October 2024, the jury deliberated for six hours.

When they came back, the forewoman read the verdict: guilty on all counts—elder abuse, fraud, theft, and breach of fiduciary duty.

The judge was a stern woman in her 60s named Patricia Morrison. She looked at Jeremy with something close to disgust.

“Mr. Foster, you are an officer of the court—an attorney. You took an oath to uphold the law, and instead, you preyed on your own elderly father. You have disgraced your profession and your family.”

She sentenced him to four years in prison. Rachel got three years.

Both were ordered to pay full restitution of $5.8 million plus punitive damages of $2 million. Their assets would be seized and sold.

The Washington State Bar would disbar Jeremy. Rachel would lose her CPA license.

I felt no satisfaction watching my son led away in handcuffs. Pearl sobbed beside me.

Even in victory, this felt like losing. But the worst was yet to come.

That night back in my apartment—my real apartment now; I’d used some of the bond money to buy a nice two-bedroom condo—I got a call from the prison. Jeremy had tried to harm himself.

He was in the medical unit, stable but under suicide watch. Pearl and I drove there immediately, but they wouldn’t let us see him.

I gave them a letter to pass to him. I don’t know what made me write it; maybe I was thinking about my father’s letter to me found after so many years.

Maybe I just needed my son to know something. The letter said:

“Jeremy, I don’t know if you’ll read this or if you’ll care, but I need you to know something. I’m angry, I’m hurt. What you did was unforgivable by any normal measure. You stole from me, lied to me, betrayed me in ways I’m still trying to understand. But you’re still my son.”

“I still remember teaching you to throw a baseball. I remember your high school graduation, how proud I was. I remember your wedding day, how happy you looked with Rachel.”

“Addiction is a disease. I didn’t understand that for a long time. In the military, we thought weakness was a choice, but I’ve learned differently.”

“You made terrible choices, Jeremy. You committed crimes. But you’re not beyond redemption. When you get out—and you will get out—there’s a place for you in this world.”

“Not in my life, not the way things were. I can’t trust you again. But I can give you something else: forgiveness. Not because you deserve it, not because what you did is okay, but because holding on to hate will poison me as surely as gambling poisoned you.”

“Your mother taught me that. She’d want me to be better than my anger. I’m using the money from your grandfather—the man who survived Pearl Harbor and taught me about sacrifice—to start a foundation.”

“The Grace Foster Foundation for Elder Abuse Victims will help people like me get legal representation, find safe housing, and rebuild their lives.”

“Pearl is joining me. She’s taking a year off school to help set it up. She’s going to become an elder law attorney like Linda. She’s going to be the person I needed.”

“I hope you find peace, son. I hope you get help. I hope one day you can look at yourself in the mirror and see someone worth respecting. But that’s your journey, not mine.”

“I’ll leave the door open a crack if you ever want to walk through it sober, honest, truly changed. We can talk. But I won’t wait for you. I’ve got work to do. Your father, Richard.”

Eighteen months later, in April 2025, I got a letter from Jeremy. He was at a medium-security prison in Monroe, working in the library and attending AA meetings and therapy sessions.

“Dad,” he wrote.

“I don’t expect you to read this. I don’t expect anything from you anymore. But I need to say this for myself. Even if you throw this letter away: I’m sorry.”

“Those words aren’t enough. They’ll never be enough, but they’re true. I’m an addict. I’ve been one for six years. It started with pain pills after my accident, and when Mom made me stop those, I switched to gambling.”

“I told myself it wasn’t as bad. Nobody gets hurt from gambling, right? Except I hurt you. I hurt Pearl. I hurt everyone who ever trusted me.”

“The worst part is I knew what I was doing. Every time I signed those transfer forms, every time I lied to you, I knew. But I told myself I’d win it back. I’d make one big score, return everything, and you’d never know. I never won. Addicts never do.”

“I think about that day you caught me stealing money from your wallet when I was 14. You sat me down and explained why it was wrong, why trust matters more than money.”