Single Dad Gave Up His Subway Seat — He Never Expected A Billionaire To Change His Life

Apartment 4C

But that was later. For now, in this moment, Ethan Brooks stood on a moving train with his daughter’s hands wrapped around a pole, his backpack heavy with unpaid bills, his boots developing a hole he didn’t have the money to fix.

“Two more stops,” he said to Maya, checking the map above the door more out of habit than need.

He knew this route the way he knew his own breathing, unconsciously, perfectly, with the deep knowledge that came from repetition and necessity. Maya nodded, her humming returning, some snippet of melody from a movie about princesses and magic and happy endings.

Ethan didn’t have the heart to tell her that real life didn’t work that way, that magic was just another name for luck, and luck was a commodity in shorter supply than subway seats during rush hour. Instead, he just held on to the pole, kept his daughter steady, and counted down the minutes until they could climb the stairs back to street level, back to their fourth-floor walk-up, back to Mrs. Chen’s soup and the evening routine that kept chaos at bay.

The train pulled into 125th Street. Ethan guided Maya toward the doors, his hand on her shoulder, his body angled to shield her from the press of boarding passengers. They stepped onto the platform together, were immediately swallowed by the crowd, just two more anonymous figures in the endless stream of New Yorkers making their way home.

Behind them, still seated, Clara Whitmore watched them go. Watched the man’s hand never leave his daughter’s shoulder, watched the daughter’s complete trust in that guidance, watched them disappear into the human river that flowed toward the stairs. The doors closed. The train moved on.

And in that moment, though neither of them knew it, though the universe gave no indication that anything significant had occurred, two trajectories had begun to intersect. Not collide, not yet. Just intersect, drawn together by the strange gravity that sometimes pulls people toward each other for reasons that won’t become clear until much, much later.

Ethan and Maya climbed the stairs from the subway platform, each step a small negotiation between momentum and exhaustion. The evening air hit them, cold enough to bite, thick with the smell of roasting nuts from a street vendor and the diesel exhaust of a bus pulling away from the curb.

“Can we get nuts?” Maya asked.

Not because she was particularly hungry, but because the question was part of their ritual, asked and answered the same way every Tuesday.

“Next week, maybe,” Ethan said.

Which was what he always said, which they both knew meant no but sounded gentler than no, left room for hope even when hope was in short supply. They walked the four blocks to their building, past the bodega with the cat that slept in the window, past the church with the sign that hadn’t been updated in 6 months, past the lot that had been under development for 3 years and showed no signs of developing into anything other than a place where windblown trash gathered in the corners.

Their building was pre-war, which was real estate speak for old and probably has mice. Six stories, brick facade that might have been handsome once but now just looked tired, fire escapes zigzagging down the front like a scar. The front door required a specific jiggle of the key and a firm shoulder against the warped wood. Ethan had the technique down.

The lobby, if you could call it that, smelled of radiator steam and someone’s dinner—something with garlic and tomato. The elevator had been broken for 8 months. The landlord kept promising to fix it; everyone had stopped believing him around month three. They climbed.

Maya counted the steps out loud until she got to 37, then switched to humming again because counting was boring and humming was not. Ethan’s knees protested around the second-floor landing, that particular ache that came from eight-hour shifts doing maintenance work at the Grand View Hotel downtown, where rich people complained that their rooms were too cold or too hot or the towels weren’t soft enough, as if the universe owed them perpetual comfort.

Fourth floor, Apartment 4C. Home. Ethan unlocked the three different locks—deadbolt, chain, and the knob lock that didn’t actually work but he kept locked anyway out of habit. The door swung open to reveal their tiny kingdom.

A railroad apartment carved out of what had probably once been a single large room. Living room that flowed into Maya’s bedroom, that flowed into Ethan’s bedroom, that flowed into a kitchen barely large enough for one person to turn around in. But it was clean. That was non-negotiable.

Ethan might not be able to afford much, but he could afford soap and elbow grease, could make sure that their small space didn’t become squalid, didn’t succumb to the entropy that poverty invited.

“Homework first, then dinner,” Ethan said, shrugging off his backpack, wincing slightly as the motion pulled at the muscle in his shoulder that had been bothering him for 2 weeks now.

“Do I have to?” Maya asked, but she was already dropping her own backpack by the small desk they’d set up in the corner of her room—a door balanced on milk crates, functional if not elegant.

“Education’s important, Maya Bird. It’s the one thing nobody can take from you once you’ve got it.”

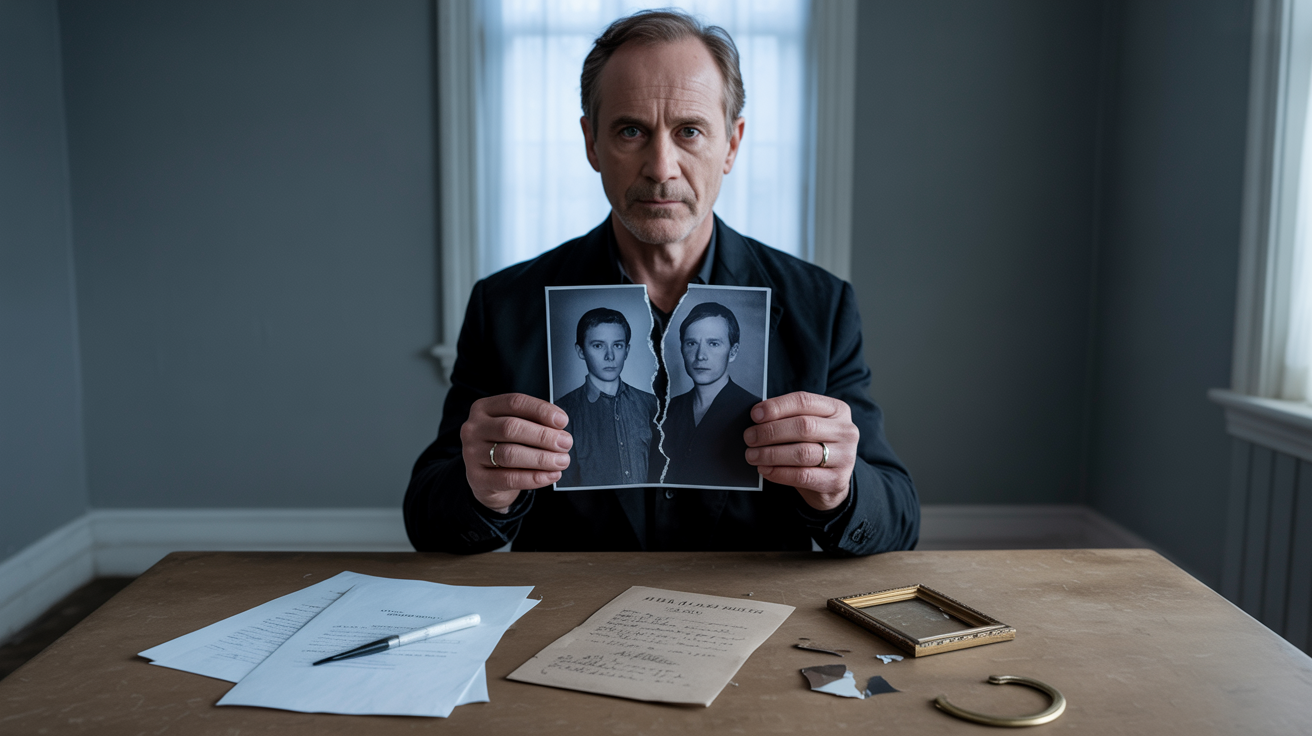

This was another ritual response, worn smooth with repetition. Jennifer had said it first, back when they’d both believed that hard work and good intentions were enough to build a life on. She’d been a teacher, had believed in education the way some people believed in God, as a force of redemption, a ladder out of whatever hole circumstance had dropped you into.

She’d been wrong, of course. Education was important, sure, but it wasn’t magic. It couldn’t stop drunk drivers from running red lights, couldn’t bring back the dead, couldn’t turn back time to the moment before everything had shattered. But Ethan kept saying it anyway because what else did he have to give his daughter except the beliefs he’d inherited from a woman who’d loved them both more than her own life?

Maya pulled out her homework folder. Spelling words this week, 20 of them, each one to be written five times. Tedious work, but necessary. Ethan had learned that education at this level was mostly about building tolerance for tedium, for following instructions, for doing what you were told even when it seemed pointless.

He moved into the kitchen, such as it was, opened the cabinet above the sink, surveyed their options. Rice, definitely. A can of beans. Some frozen vegetables that were probably still good, though the bag had that frostbitten look that suggested they’d been in the freezer longer than optimal.

Mrs. Chen’s soup would help. She was on the second floor, had lived in this building for 30 years, had watched the neighborhood change and change back and change again. She’d known Jennifer, had cried at the funeral, had quietly adopted Ethan and Maya into her circle of care in the way that some people did, that network of mutual support that developed in buildings like this where everyone was struggling and so everyone understood.

There was a knock at the door, soft, three taps. That was Mrs. Chen’s signature. Ethan opened up.

Mrs. Chen stood there, tiny and wrinkled and indomitable, holding a container of soup that was still steaming.

“I made too much,” she said.

Which was what she always said, which was transparently untrue but allowed everyone to maintain dignity.

“You help me, okay? I cannot eat all this.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Chen,” Ethan said, accepting the container with both hands.

The warmth of it seeped through the plastic into his palms, a small comfort that was larger than its size.

“Maya doing homework?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Good girl. Smart girl.”

Mrs. Chen peered past him into the apartment as if checking to make sure everything was in order, that Ethan was holding things together. Satisfied with whatever she saw, she nodded.

“You working tomorrow?”

“Every day this week.”

“You look tired.”

Ethan almost laughed at that. Tired was his baseline now, the default setting of his existence.

“I’m okay.”

Mrs. Chen’s expression suggested she didn’t believe him, but she didn’t push. That was the thing about Mrs. Chen: she helped, but she didn’t pry. She understood the delicate balance between support and intrusion, knew instinctively where that line fell.

“You need anything, you knock, okay?”

She was already retreating toward the stairs, moving with the careful deliberation of someone whose bones ached but whose spirit refused to acknowledge it.

“Thank you,” Ethan said again.

Because there weren’t enough ways to say thank you, weren’t enough words to encompass the gratitude he felt toward the people like Mrs. Chen who kept him and Maya afloat. He closed the door, carried the soup to the kitchen, began the familiar choreography of preparing dinner. Rice in the cooker, soup reheated on the stove, frozen vegetables microwaved. It wasn’t elaborate, but it was hot and it was nutritious and it would fill their stomachs for another night.

In her room, Maya worked through her spelling words with the intense concentration that six-year-olds brought to tasks they took seriously. Ethan could hear her muttering under her breath, sounding out syllables, her pencil scratching against the paper.

He pulled the bills from his backpack while the soup heated. Might as well face them now, get it over with. Three envelopes: electric, medical, and something from Maya’s school about the spring trip to the science museum.

Electric past due, threatening disconnection if not paid within 10 days. Medical still climbing from Jennifer’s hospital stay 3 years ago, that nightmare of bills that seemed to multiply like cancer cells metastasizing through his financial life. School trip, $45, which might as well have been $400 for all the likelihood he had of pulling it together.

Ethan set the bills aside, face down, as if not looking at them would somehow make them less real. He’d figure it out. He always figured it out through some combination of extra shifts and skipped meals and careful negotiation with creditors who were used to people like him—people who were trying, who just didn’t have enough to spread across all the cracks in their lives.

The soup was ready. He called Maya to dinner. They sat at their small table—another door-on-crate situation, covered with a vinyl tablecloth that Maya had picked out because it had sunflowers on it and sunflowers were happy.

“How was school today?” Ethan asked, which was what fathers were supposed to ask even when they could guess the answer.

“Good. We learned about butterflies. Did you know they can taste with their feet?”

“I did not know that.”

“It’s true. Miss Robert showed us a video. They land on flowers and can tell if it’s good to eat just by standing on it.”

Maya demonstrated with her hand, landing her fingers on the table like butterfly feet.

“Imagine if we could do that. You could just step on your dinner and know if it was good.”

Ethan smiled despite everything, despite the bills and the exhaustion and the general weight of keeping their small ship afloat. This was why he did it, all of it. These moments. His daughter enthusiastic about butterflies, unaware that the world was harder than it should be, still young enough to find wonder in simple facts.

They ate Mrs. Chen’s soup—chicken and vegetables and rice noodles, simple and perfect and tasting like someone cared. They talked about butterflies and spelling words in the book they were reading together before bed, a chapter each night, currently in the middle of some story about a mouse who went on adventures that seemed wildly inappropriate for a creature that size.

After dinner, Ethan washed dishes while Maya changed into her pajamas. Bath night was every other day; water was expensive and anyway Maya was six, she wasn’t getting that dirty. Teeth brushing was non-negotiable though, 20 seconds on each quadrant of her mouth, a routine they’d established when her first baby tooth had fallen out and the dentist had given them the stern talk about cavity prevention.

Then the best part of the day: reading time. Ethan settled into the chair beside Maya’s bed, a chair he’d found on the curb three blocks away and had carried home on his back, had cleaned until it was safe, had positioned right there so he’d have a place to sit during these nightly rituals. Maya burrowed under her covers, clutching the stuffed rabbit that had been hers since birth, that was missing one eye and had been re-stuffed at least twice but remained her most prized possession.

They read chapter 7, in which the mouse encountered a cat who surprisingly did not want to eat him but instead wanted his help retrieving something from a high shelf. It was a silly story, implausible on multiple levels, but Maya loved it and that was enough.

After reading, they did their other ritual: three good things from the day.

“I’ll start,” Ethan said. “One: Mrs. Chen’s soup. Two: watching you work so hard on your spelling. Three: right now, this.”

Maya considered, her face serious.

“One: learning about butterflies. Two: the soup, yeah. Three: when you gave that lady your seat on the train. That was really nice, Daddy.”

Ethan felt that warm painful thing in his chest again, that complicated pride-sorrow cocktail.

“Just trying to do right, sweetheart.”

“I know. That’s what makes it nice.”

He tucked her in, kissed her forehead, turned on the nightlight that cast dancing shapes across the ceiling—another curb find, this one from two years ago, a small lamp shaped like a carousel that Maya had declared the most beautiful thing she’d ever seen.

“Love you, Maya Bird.”

“Love you, Daddy.”

He left her door cracked open—she didn’t like complete darkness—and retreated to the living room. Now came the hard part of the day, the hours between Maya’s bedtime and his own, when he had to face the bills and the budget and the impossible mathematics of making not enough stretch across too many needs.

Ethan opened his laptop, 7 years old, running an operating system that was three versions behind but functional. He pulled up his spreadsheet, the one where he tracked every dollar, every expense, every impossible decision about what got paid and what got pushed to next month.

Electric: couldn’t skip that, not with winter coming. Medical: he’d call tomorrow, try to negotiate another payment plan, another extension. School trip: that was the hardest one. He’d have to tell Maya she couldn’t go, would have to watch her try to hide her disappointment, would have to feel like he’d failed her even though he was doing everything humanly possible.

Unless.

Unless he picked up extra shifts. The hotel was always looking for people willing to work overnights, the graveyard shift that paid an extra $1.50 an hour. If he could string together three or four of those next week on top of his regular schedule, maybe he could scrape together the $45.

He’d be exhausted, would barely see Maya, would be running on fumes and coffee and sheer willpower. But she could go on the field trip, could spend a day at the science museum with her class, could experience something beyond their small apartment and the walk to school and the subway rides to nowhere in particular.

It was worth it. She was worth it. Ethan added the shifts to his calendar, already feeling the exhaustion they’d bring, already making peace with the cost. This was fatherhood: an endless series of calculations about what you could sacrifice to give your child something approaching normal.

He worked on the budget until midnight, moving money around like puzzle pieces, trying to make them fit into a picture that looked like solvency. It never quite worked, but he got close enough. Close enough to keep the lights on, to keep food in the cabinet, to keep them moving forward one day at a time.

Finally, exhausted beyond measure, Ethan closed his laptop. He checked on Maya one last time. She was sleeping soundly, her rabbit tucked under her chin, her face peaceful in the way that children’s faces were peaceful, unmarked by the worries that carved themselves into adult features.

He stood in her doorway for a long moment just watching her breathe. This was everything. This small person, this beautiful human he’d helped create, this responsibility that was heavier and more precious than anything he’d ever carried.

“I’m doing my best,” he whispered into the darkness. “To Jennifer, to God, to whoever might be listening, I promise I’m doing my best.”

The apartment didn’t answer. The city rumbled on outside, 8 million people living 8 million lives, most of them struggling in ways large and small, all of them carrying burdens that no one else could see. Ethan went to his own bedroom, set his alarm for 5:30 a.m., lay down on his mattress on the floor—the bed frame had broken a year ago and hadn’t been a priority to replace—and closed his eyes.

Sleep came slowly, the way it always did when your mind wouldn’t stop cataloging problems and your body wouldn’t stop aching from the day’s labor. But eventually exhaustion won, eventually he drifted off into dreams that he wouldn’t remember, that featured Jennifer sometimes, her face already starting to blur around the edges, her voice not quite as clear as it used to be.

And across the city, in a penthouse in Tribeca, Clara Whitmore stood at her window with a glass of scotch and stared out at the lights, unable to stop thinking about a man who’d given up a seat on a subway train. Two people, two lives, two trajectories intersecting.