The Doctors Laughed At The “New Nurse” — Until The Wounded SEAL Commander Saluted Her.

The Bet Behind Her Back

They called her the janitor behind her back. Dr. Sterling, the hospital’s arrogant golden boy, actually placed a $500 bet that the new middle-aged nurse wouldn’t last a week at St. Jude’s Elite Trauma Center. She moved too slowly. She checked charts too obsessively. She didn’t fit the sleek, high-tech image of modern medicine.

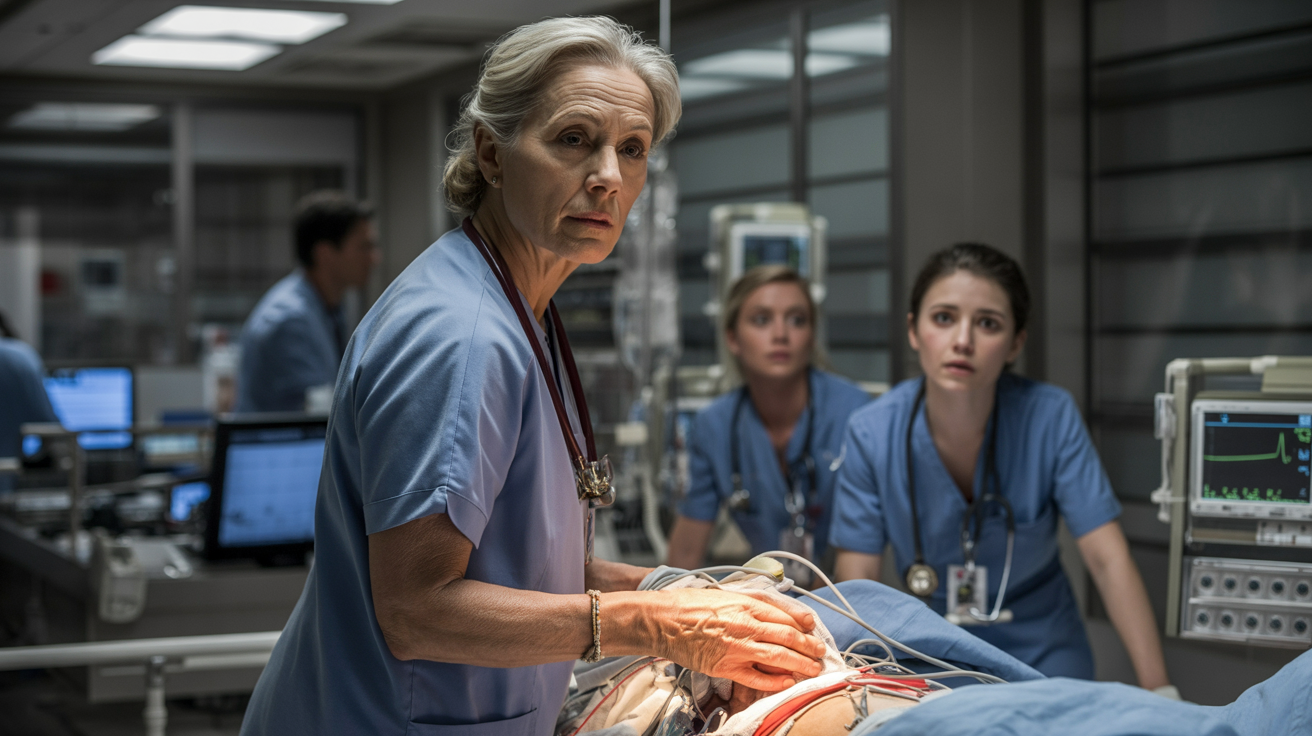

But the laughter died the night the doors burst open and a critical Navy SEAL unit was wheeled in. Because the dying commander didn’t look at the chief of surgery; he looked at the trembling new nurse, fought through the anesthesia, and raised a shaking hand to his brow. What happened next didn’t just silence the room; it ended careers.

The fluorescent lights of St. Jude’s Military Medical Center in Virginia hummed with an aggressive brightness, illuminating the sleek stainless steel surfaces of what was arguably the best trauma unit on the East Coast. It was a place for the best of the best. The doctors here weren’t just physicians; they were gods in white coats, groomed for greatness, boasting degrees from Harvard and Johns Hopkins.

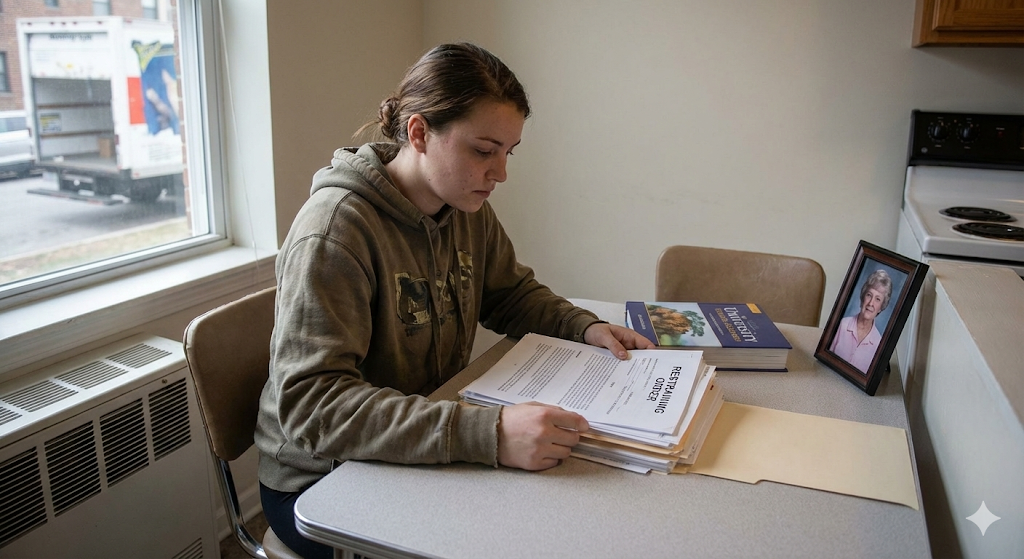

And then there was Sarah. Sarah Miller stood by the supply cart in Trauma Bay 4, slowly restocking IV bags. She was 52 years old with graying hair pulled back into a severe, unfashionable bun. Her scrubs were a size too big, hiding a frame that looked tired.

She didn’t move with the frantic, caffeinated energy of the younger nurses who sprinted down the halls in their tight Figs scrubs. Sarah moved with a deliberate, plodding pace that drove the residents insane.

The Arrogant Chief Resident

“Check the expiration dates again, Sarah,” Dr. Preston Sterling called out from the nurse’s station, not bothering to look up from his tablet.

He was 32, handsome in a jagged, sharp way, and the son of a senator. He was the chief resident, and he made sure everyone knew it.

“I checked them 10 minutes ago, Doctor,” Sarah said, her voice raspy like she had spent too many years shouting over noise.

“We’ll check them again,” Sterling smirked, winking at the nurse beside him, a young woman named Brittany who spent more time fixing her eyeliner than checking vitals.

“We can’t have our patients dying because Grandma forgot to read the label. Dementia is a silent killer, you know.”

Brittany giggled, covering her mouth. “You’re terrible, Dr. Sterling.”

“I’m just cautious,” Sterling said loudly, ensuring the entire floor could hear. “HR keeps sending us these charity cases. I mean, look at her hands. They shake.”

It was true; Sarah’s hands had a faint, rhythmic tremor. It was subtle, but to a surgeon like Sterling, it was a glaring neon sign of incompetence. Sarah didn’t respond. She just gripped the saline bag tighter, her knuckles turning white, and continued her work.

She had only been at St. Jude’s for three weeks. In that time, she had been assigned the worst shifts, the messiest cleanups, and the most menial tasks. They treated her like a glorified maid who happened to have an RN license.

“I heard she used to work at some rural clinic in Nebraska,” Another resident, Dr. Cole, whispered loudly. “Probably put Band-Aids on scraped knees for 30 years. Now she thinks she can handle Tier 1 trauma care.”

“She won’t last,” Sterling said, finally standing up and smoothing his pristine white coat. “I give it two more days. One real emergency, one massive hemorrhage, and she’ll faint. Then we can get her out of here and get someone who actually belongs in the 21st century.”